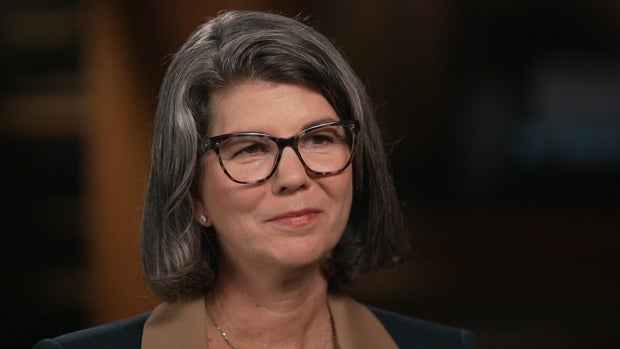

Amy Sherald on her portraiture, her subjects’ gaze, and the impact of painting Michelle Obama’s portrait

When Amy Sherald was selected to paint the official portrait of Michelle Obama eight years ago, many people in the art world didn’t know who she was. They do now. At 52, Sherald has become one of America’s most celebrated painters. She’s had two major museum retrospectives this year and was supposed to have a third this month at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. But Sherald canceled it, concerned, she says, that museum officials, already under pressure from the Trump administration, were going to try and censor a painting. The controversy made headlines, but Sherald has faced much bigger challenges than that. Like many of the people she paints, Amy Sherald has found a way to make her way.

In Amy Sherald’s paintings, her subjects — Black Americans — stare silently straight out from the canvas. There is something in their eyes that draws you in, something knowing in their gaze. They appear unapologetic, unafraid, posed against monochromatic backgrounds, or in scenes as bright and bold as they are. In this painting, a farmer leans atop an impossibly pristine John Deere tractor, surrounded by blue sky and green grass.

Anderson Cooper: In so many of your paintings the subject is looking out at the viewer.

Amy Sherald: I think that’s important, I don’t think these portraits are confrontational, but they are present. And they do want you to sit with them and have an exchange.

Amy Sherald: They have jobs. They’re doin’ their jobs, you know? They’re being beautiful, they’re being colorful. But they also have work to do in the world.

Anderson Cooper: And they’re doing that work in your painting?

Amy Sherald: By standing there and being present, and looking at you, and meeting your gaze. That’s the work.

Amy Sherald: They don’t have to say anything. But every time you look at that portrait, something is happening inside of you.

60 Minutes

Amy Sherald’s work hangs in the most prestigious museums in America, and in the rooms of major collectors, and some smaller ones, including me. This summer she gave us a private tour of her show “American Sublime” while it was at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, home to some of the greatest artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. Sherald has been dreaming of having a show here for years.

Amy Sherald: I would sit in my studio every day. And I would meditate and visualize myself in this space.

Anderson Cooper: How does it compare to the fantasy?

Amy Sherald: It’s exactly like it.

Anderson Cooper: Is it?

Amy Sherald: Yeah, it’s perfect.

Her paintings are portraits, but not in the traditional sense. The people in them are real, but their names are rarely used. She’s cast them in a visual story all her own.

Amy Sherald: The process starts with a photograph. After I randomly come across some person that, I like to say, like, my energy recognizes their energy, or there’s something there, right? They come to the studio and either I already have a vision in my head of what I wanna create, or they are the walking vision of what I want to make. And I photograph them.

She’s used friends, models, dancers, strangers she’s seen on the street. The clothes they wear are often thrift store finds. Sherald has racks of them in her studio.

Amy Sherald: I’ve had this for probably five years. Just waiting for the right person.

There were only two paintings in Sherald’s show of people whose names were used. This is her portrait of a very alive Breonna Taylor, painted after she was shot to death by police in 2020 in a botched raid on her apartment. And this is Sherald’s most famous work, the former first lady titled “Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama.” Unveiled in 2018, it made headlines around the world.

Anderson Cooper: Did you know how important this was going to be for your career?

Amy Sherald: Yes.

Anderson Cooper: Did you think about that?

Amy Sherald: I think in the moment I wasn’t thinking about that. Because if I did I probably would’ve just freaked out, you know? I just stayed outta my head and stayed in the painting.

Anderson Cooper: What stands out to you?

Amy Sherald: When I look at it now? The dress. Like, I’m deeply in love with this dress. Just the red, the pink, the yellow, and then the black and gray. I wanted the dress to also have some kind of symbolism, and almost be a painting in and of itself.

Before coming to the Whitney, “American Sublime” was at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Sarah Roberts was the show’s curator.

60 Minutes

Anderson Cooper: I wasn’t sure we could do Amy Sherald for 60 Minutes because I’m not sure that cameras really capture the work. It’s a very different experience to see it in person. There’s a luminescent quality to it.

Sarah Roberts: Yes. There’s a quality to the color that is impossible to catch on camera. They have a majesty and a tactility, when you see them in person that they lose in, in reproduction.

Anderson Cooper: How does she do that?

Sarah Roberts: She’s an incredible painter. I mean, just the–

Anderson Cooper: –that’s what it comes down to.

Sarah Roberts: technical skill.

Sherald’s style of painting is called American Realism.

Sarah Roberts: It’s a way of depicting the ordinary in American life. It has meant slightly different things to the different painters it’s been applied to and she is creating images that say something about America right now. Ideas of freedom, ideas of individualism, freedom of expression, and a lot of kind of Americana ideas. You know there’s the cowboy, and the beauty queen, and the white picket fence. She’s reimagining them, and redeploying them to make sure that that idea of America includes everyone.

Anderson Cooper: Everybody has a seat at the table?

Sarah Roberts: A place on a museum wall.

It was this painting on a museum wall that Amy Sherald says changed her life. She saw it on a class trip to the city art museum in Columbus, Georgia, when she was a teenager. It was painted by an American artist named Bo Bartlett.

Amy Sherald: There was figure in it that was an image of a Black man. And I realized in that moment that I had never seen a Black person in a painting before.

Anderson Cooper: In any painting you had not seen a Black person.

Amy Sherald: In any painting.

Anderson Cooper: What did you think?

Amy Sherald: I thought, “I want to do this, too.”

Anderson Cooper: You knew in that moment? You thought that I want to do this?

Amy Sherald: 100%. 100%. “Click!” It turned on the light.

Her parents – Amos and Geraldine Sherald – hoped she’d be a doctor, but in college she broke the news to them she was going to devote her life to art. She spent more than a decade painting by day and waiting tables at night.

Anderson Cooper: Did you ever think this is not gonna work out?

Amy Sherald: Yeah. But I, I couldn’t give up. Like I always say, the world is full of quitters. And most people don’t want the discomfort. And most people don’t want the risk. So, if I kept at it, then eventually, something would have to happen.

60 Minutes

What happened was not what she expected. Sherald – an avid runner – was training for a triathlon in 2004, when she was diagnosed with a rare heart condition.

Amy Sherald: My doctor said, “You’re lucky to be alive.” He basically said like, “Don’t do anything to get your heart rate up because you could have a tachycardic episode and you could die.”

She nearly did, eight years later. She collapsed in a drug store, and spent months in the hospital, before receiving a heart transplant. She was 39 years old.

The donor was a young woman named Kristin Lin Smith.

Anderson Cooper: Does it feel different to have, somebody else’s, heart?

Amy Sherald: It doesn’t anymore. But it does, I’d say, for, like, the first five years.

Anderson Cooper: Wow. For five years?

Amy Sherald: Yeah. You think about it a lot. I have moments where I think of her. And they’re usually when I’m doing something that I wouldn’t have been able to do. So, like, whenever that happens, I have on my Instagram account, I hashtag it “adventures of Kristin and Amy” so that I can mark all the big moments and include her in those moments. And when I sign my name, I put a little heart on the end for her.

Anderson Cooper: So she lives in all your paintings?

Amy Sherald: She does. Yeah.

Amy Sherald’s studio is in this warehouse in New Jersey. She makes about a half dozen new paintings here a year. In a closet, there’s a wall full of paints, in colors she’s mixed herself.

Amy Sherald: This is the grayscale that I paint from, when I’m doing the skin.

Skin color in her portraits is something Sherald has given a lot of thought to. If you hadn’t noticed, she doesn’t use brown or black. She paints her subjects’ skin in shades of gray.

Amy Sherald: Right now, we’re in the mid-tone phase, where I’m still shaping the face.

At first, she says, she just liked the way the gray looked. It reminded her of old family photographs she grew up with — this one is of her maternal grandmother.

Anderson Cooper: You want somebody to see the humanity in your subject?

Amy Sherald: I think that’s where it starts. That’s why I chose to use the grayscale instead of brown skin. I think that it offers the viewer an opportunity to pause and consider something else before we get to that.

Anderson Cooper: If they had brown skin in your painting, would that be the first thing that people noticed?

Amy Sherald: I think so. I mean, I think we still look at each other through our phenotypes anyway.

Anderson Cooper: Phenotypes is what?

Amy Sherald: Phenotypes are your eyes, your nose, your lips. Like, you know, you can look at somebody and say like, “Oh, OK, this person’s probably Caucasian and this person is probably not Caucasian,” you know? But they look Black. I can’t take Blackness away from them. But the lack of color allows for a different entry point.

Anderson Cooper: When did you realize that?

Amy Sherald: When I became afraid to paint Brown people, because I was afraid that the work would be marginalized and not be able to be in conversation with other artists. Just it’d be put in the Black corner.

That certainly seems unlikely now. At auctions, her paintings have sold for as much as $4 million, and are often compared to work by the masters of American Realism: Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth, even Norman Rockwell.

Anderson Cooper: Does that make sense to you in any way?

Amy Sherald: It’s technically what I wanted, as a Black woman artist, American for people to be like, “Yeah, Amy Sherald, Norman Rockwell, Edward Hopper.” Like, I’m in the room with the guys. And so, I think I’m OK with it. Yeah, I think I’m OK with it.

Anderson Cooper: Not a bad room to be in.

Amy Sherald: No. Yeah.

Before we left her studio, Sherald showed us this model made in preparation for the now canceled exhibition of “American Sublime” at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Amy Sherald: You get to see how it flows. And then, what kind of story it’s telling as the viewer walks through.

She told us she backed out of the show in July, after learning Smithsonian officials were concerned about this painting of a trans person posing as the Statue of Liberty, and wanted to display it alongside a video they said would, in their words, “contextualize the piece.” The Trump administration had for months been criticizing the Smithsonian as being too woke, and promised to review its exhibitions. When Sherald canceled, the White House applauded, calling the painting – quote – “divisive and ideological.”

Amy Sherald: There were conversations about the work being censored. The show was “American Sublime.” It was a whole narrative. And a trans woman is a part of that narrative for me. Any kind of contextualization around the work would have been unacceptable, and it would’ve deviated from how the work was originally conceived. And because of that, I felt like my only choice was to pull out.

Anderson Cooper: Do you see your work as political?

Amy Sherald: Today I do. I don’t think that its, in its true nature from where it comes from inside of me political. But it lives in the world. And therefore, can be art on Monday and political on Tuesday, you know?

Sherald’s paintings won’t be hidden away for long. After she canceled the show in Washington, The Baltimore Museum of Art offered to exhibit “American Sublime.” The show opens there Nov. 2.

Anderson Cooper: Do you consider the work patriotic?

Amy Sherald: Yes.

Amy Sherald: I don’t think there’s anybody more patriotic than a Black person.

Anderson Cooper: How so?

Amy Sherald: I mean, we’ve been here since the inception of this idea of what American is. We are deeply ingrained in the fabric of this country. This country would not be if it was not for us. So I have to claim that patriotism. Otherwise, I’m just handing it over to somebody to give me the definition of what it means to be American. But I know what the definition of what it means to be an American is. And I’m the definition of an American.

Produced by Graham Messick. Associate producer, Alex Ortiz. Broadcast associate, Grace Conley. Edited by Michael Mongulla.