Siblings torn apart by Argentina’s dictatorship find each other

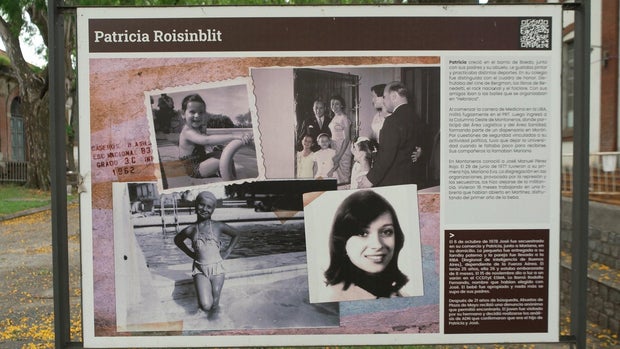

Mariana Eva Perez always knew she had a brother. Her parents, Patricia Roisinblit and José Manuel Pérez Rojo, were kidnapped by Argentine military death squads when she was a baby in October 1978.

Patricia, a 25-year-old student in medical school, was 8-months pregnant at the time, and gave birth in one of the military’s clandestine death camps known as ESMA, the Navy School of Mechanics. Before she was killed, she named her baby Rodolfo.

In 2000, 60 Minutes correspondent Bob Simon reported on Mariana and her grandmother Rosa’s decades-long search for Rodolfo. He was one of an estimated 500 babies born in death camps to mothers who were kept alive only long enough to give birth before being killed.

A systematic campaign to snatch babies

The babies, in a systematic campaign, were then given to childless military couples. The Argentine government and human rights organizations estimate that between 15,000 to 30,000 people were killed or “disappeared” during the junta’s dictatorship that lasted from 1976 to 1983.

60 Minutes

Miriam Lewin, an Argentine journalist who was kidnapped in 1977 when she was a student activist and later taken to ESMA, remembered Patricia Roisinblit after she gave birth to her son.

“He was a beautiful and healthy baby boy, almost blond, and she told me, ‘His name is going to be Rodolfo,’ and she was smiling,” Lewin told Bob Simon in 2000.

The Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the search for Rodolfo

Patricia Roisinblit was never seen again, nor was her husband. Her mother, Rosa Roisinblit, together with Mariana, spent years searching police stations, hospitals and orphanages for baby Rodolfo but never found him.

60 Minutes

Rosa, now 105, became a founding member of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a group of women who spent years demanding answers about their missing grandchildren. The group has found over 130 appropriated babies since the 1980s.

When Bob Simon asked Mariana about her missing brother in 2000, she said: “I have a lot of hope that he comes to realize that he’s been living a lie and that he would come looking for me.”

A tip that leads to finding her missing brother

Just days after that interview with 60 Minutes, Mariana received a promising tip about a young man that might be her brother. His name was Guillermo Gomez, and he worked at a fast-food restaurant.

“At that moment… I felt, I felt dissociated,” Mariana recalled during an interview. “I had a feeling of peace and relief and that everything would be OK.”

She passed him a note that read: “My name is Eva Mariana Pérez, I am the daughter of desaparecidos. I’m looking for my brother. I think he might be you.” Along with the note, she left him a photo of her parents.

Guillermo was stunned when he saw the photo of Mariana’s father, José.

“It’s like in a science fiction movie when you see a picture of yourself in the past,” he said. “It was a picture of me in the past. I didn’t feel that Mariana’s father just looked similar, but identical.”

A photograph of a man that looked like him was one thing, but only a DNA test could confirm his real parentage. “I was very afraid,” Guillermo said. “At that moment, I didn’t know who I was.”

Reckoning with a new identity and family

The test results were conclusive, he was Mariana’s brother. But there was another truth to face: the couple that raised him, Francisco Gómez and his wife Dora Jofre, had not only appropriated him, but the man he called his father was likely involved in his real parents’ kidnapping and deaths.

“I was born in captivity like a zoo animal,” Guillermo, who changed his last name to Pérez Roisinblit, said in an interview. “My mother was also kidnapped. I was separated after three days. I disappeared for 21 years. I am a contradiction because I am a disappeared person alive. I am a person who was missing without knowing I was missing.”

60 Minutes

Guillermo said Gómez was abusive, and he had an unhappy childhood. He felt differently about Jofre, who he said always tried her best to take care of him.

“I grew up being afraid of him, running away from him,” Guillermo said. “And she, for a long time, was practically my whole world. She was the person I called mom.”

His relationship with his mother was a source of conflict with his newfound sister Mariana and grandmother Rosa. Guillermo didn’t want Jofre to go to jail. But his sister and grandmother said it felt like a betrayal. They wanted consequences.

“Every day, every morning, she knew she had stolen someone else’s son,” Marian said. “And I don’t forgive that. They stole my brother and they stole him from me for the rest of my life.”

Jofre was tried and sentenced to three years imprisonment for Guillermo’s abduction.

In 2016, Guillermo faced Gomez, the man he once believed was his father, in court. When he took the witness stand, he made one final plea.

“I told him I needed to stop being in constant mourning for the death of my parents and that I needed to know when it happened, who had been responsible for their deaths and where their remains are,” Guillermo said. “And he chose to say nothing.”

Gómez was sentenced to life in prison.

“I wish this had a happy ending.”

After the trial, the siblings presented a unified front with their grandmother Rosa, but their relationship floundered. They had little in common, apart from DNA. They were, after all, separated for two decades. There were also struggles familiar to many siblings: jealousies, resentments and issues with money.

“Life isn’t a movie. I wish it was a Hollywood production and this had a happy ending,” Guillermo said. “Having been raised separated, not living together, we could never get over that distance between us.

Guillermo is now a human rights lawyer and working with the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, taking up his grandmother’s work to help find children who were stolen and appropriated during the dictatorship.

Mariana is a writer, playwright and academic. Despite her difficult relationship with her brother, she’s never regretted finding him.

“What happened broke everything, so what’s broken is broken,” she said. “It’s very difficult for us as a society to accept that it’s broken forever. But it’s always better to know the most painful truth than not knowing the truth at all.”